Riddler Numistmatics

Sep 29, 2017

If a puzzle involves flipping coins, then it is typically a good candidate for "solution by simulation". This problem, from the weekly fivethirtyeight riddler classic was fun because it involved equal parts probability theory and computation.

On the table in front of you are two coins. They look and feel identical, but you know one of them has been doctored. The fair coin comes up heads half the time while the doctored coin comes up heads 60 percent of the time. How many flips — you must flip both coins at once, one with each hand — would you need to give yourself a 95 percent chance of correctly identifying the doctored coin?Extra credit: What if, instead of 60 percent, the doctored coin came up heads some P percent of the time? How does that affect the speed with which you can correctly detect it?

Let's start with the base case, in which a single coin has a 60% probability of landing on heads. Let's define two probability functions for each coin, and .

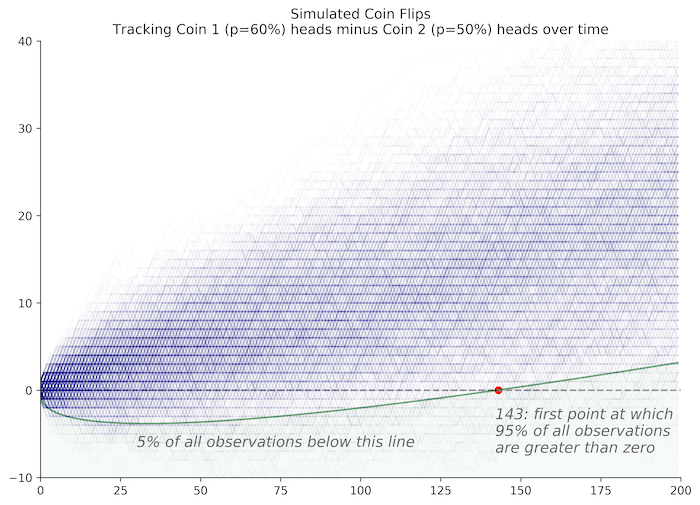

We are really interested in a new variable, , which is the difference between and , tracked cumulatively over time. Therefore, at each point in time, can be incremented by 1, 0, or -1.

can be simulated using python extremely efficiently using the following code. We are interested in the number of flips it will take for to be positive 95% of the time. Because one coin is biased towards heads we know that will be biased toward positive numbers over time. Therefore, our task is to identify the number of flips it takes for 95% of all scenarios to result in a positive value for .

One way to do this is to flip coins a fixed number of times and record the value of after the final flip. The advantage in this approach is that we can vectorize this operation and run it very quickly. The disadvantage of this approach is that we have to predefine the number of flips we're interested in testing. If we don't test enough, then we may not gather enough evidence to achieve 95% certainty that a given coin is biased. The code below uses a default of 200 flips, which we find is plenty to meet our goal.

import numpy as np

def model(simulations, flips=200, p1=0.6, p2=0.5):

p = [p1*(1-p2),p1*p2+(1-p1)*(1-p2),(1-p1)*p2]

out = np.random.choice([1,0,-1],size=(trials,flips),p=p).cumsum(1)

return out

trials = 1000000

X = model(trials)

np.where((X > 0).sum(0) > 0)[0][0] + 1

>>> 143

Why do we check our distribution against the zero line? As long as there is a meaningful probability of , we can't rule out the likelihood that the coins have equal probabilities. However, as soon as 95% of our simulations lie above zero, we can be 95% confident that one of the coins is biased.

We can also extend this problem to test coins with different biases. With , it takes 143 flips to detect the doctored coin. With higher values of , we can detect the doctored coin sooner. With lower values of it takes many more trials. In general, we can use the normal approximation of our distribution, with mean and variance . Using a confidence test at 95%, we can solve for the number of flips it would take to identify a doctored coin with any .

For example, the normal approximation in our case has mean and variance . We can confirm that is positive after 143 flips by dividing the mean by the square root of the variance and testing at the 95% confidence level: 1.645. Because , we confirm our result.