Riddler Circles

Apr 19, 2019

Introduction

The Riddler this week asks us about random points on the edge of a circle. Specifically, if we generate random points around the circumference of a circle, how likely are those points to fall on only one side? Our answer should be a function of . Here is the full text.

If N points are generated at random places on the perimeter of a circle, what is the probability that you can pick a diameter such that all of those points are on only one side of the newly halved circle?

Starting with intuition

It's possible to build an intuitive sense of our answer by examining a few values of . For example, by definition, a single point, , must always be true: a single point is always on its own side. Therefore the odds are 100%.

For , let's take the case that the points are on exact opposite ends of the circle - for example at the "9 o'clock" and "3 o'clock" positions, respectively. Those points will lie on the same bisecting line of the circle, and I think it's fair to say they should both be considered to be on the same side of the circle. In any other case of randomly generated points, they will be even closer, so it's trivial to show that they will lie on the same side of the circle. Again, our odds are 100%.

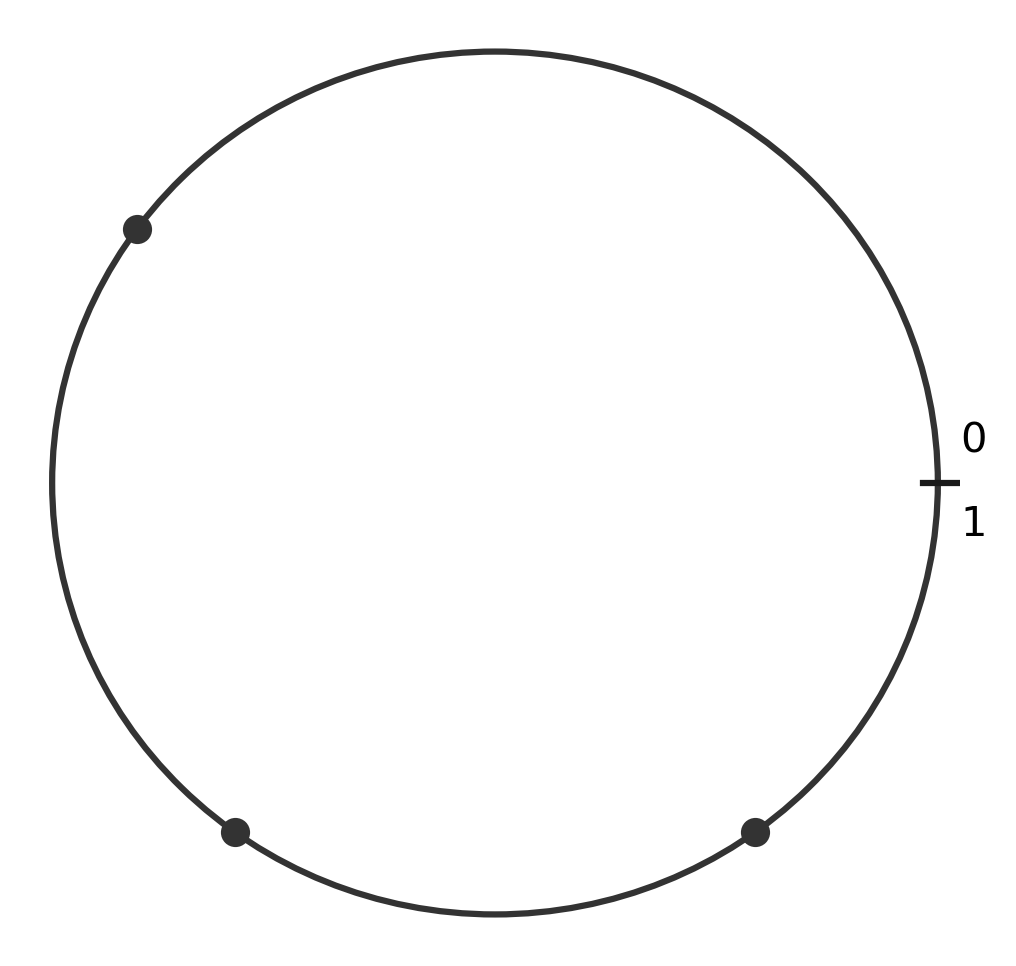

When it becomes more complicated. Because we're dealing with randomly generated points, we can always "spin" our circle around to fix one point in any position we like. For example, we can assume we will always have a point at the "3 o'clock" position. Our next point can be anywhere on the circle, but by similar logic we can maneuver our circle so this next point is on the top half. Given these two points, we can define the valid region of the circle's circumference that satisfies our problem. For example, if the second point is at the "12 o'clock" position, then our third point must be located anywhere except between "3 o'clock" and "6 o'clock" to satisfy our criteria. This will happen 75% of the time.

If the second point is located directly on top of our first point, then we have virtually 100% likelihood of satisfying our criteria. If the second point is located directly across from our first point, then we have 50% likelihood. Therefore, we can take the average of these two values to show that for , the overall likelihood is 75%.

From here, the cases get far more complicated, so I opted to let my computer do the hard work for me! Our single sanity check is that we would expect probabilities to decrease as increases. As we generate more points, we expect them to cover more of the circle's circumference, making it less likely that they would be clustered on a single side.

Coding a simulation

In order to solve this problem through simulation, we need to define our program instructions. We need a way to generate random points on a circle, and a way to check whether our points lie on the same side or not.

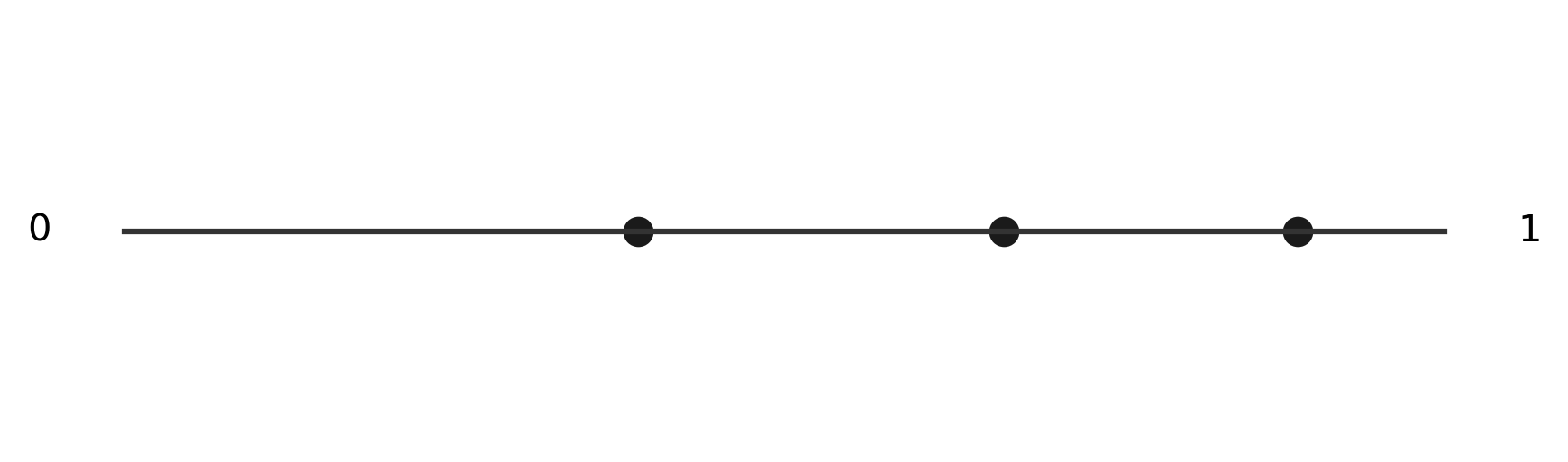

Generating random points - any point on the circle can be uniquely identified by its angle, which is a number between 0 and 360 (for degrees), or between 0 and (for radians). We can also simplify this even further and say a point is uniquely identified by a number between 0 and 1, which can be translated into an angle by multiplying by either 360 or by .

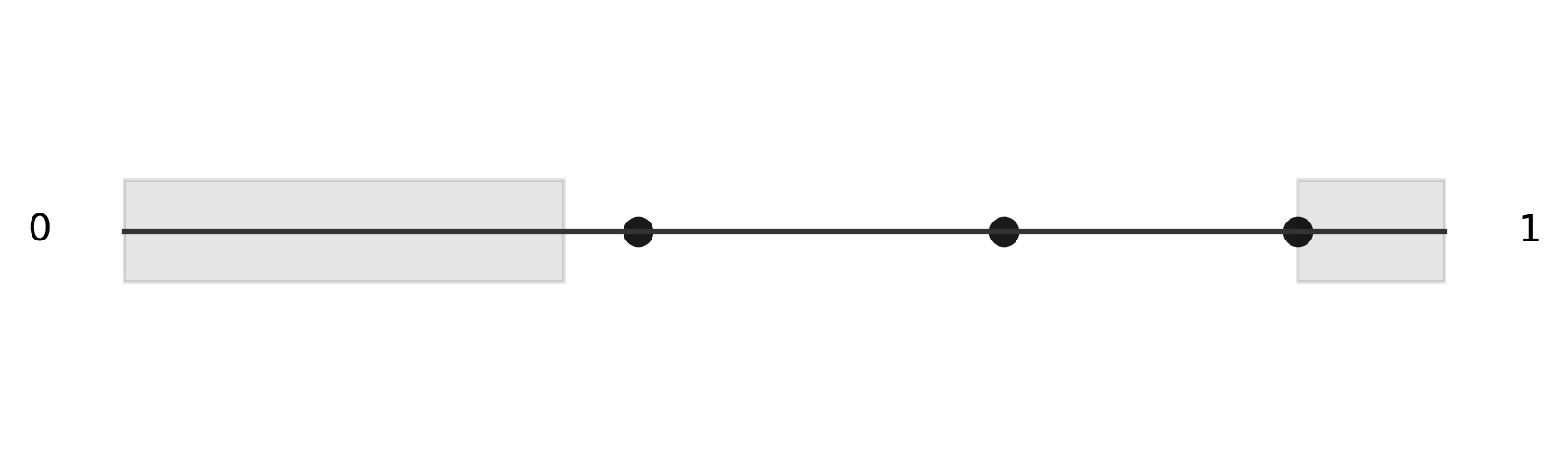

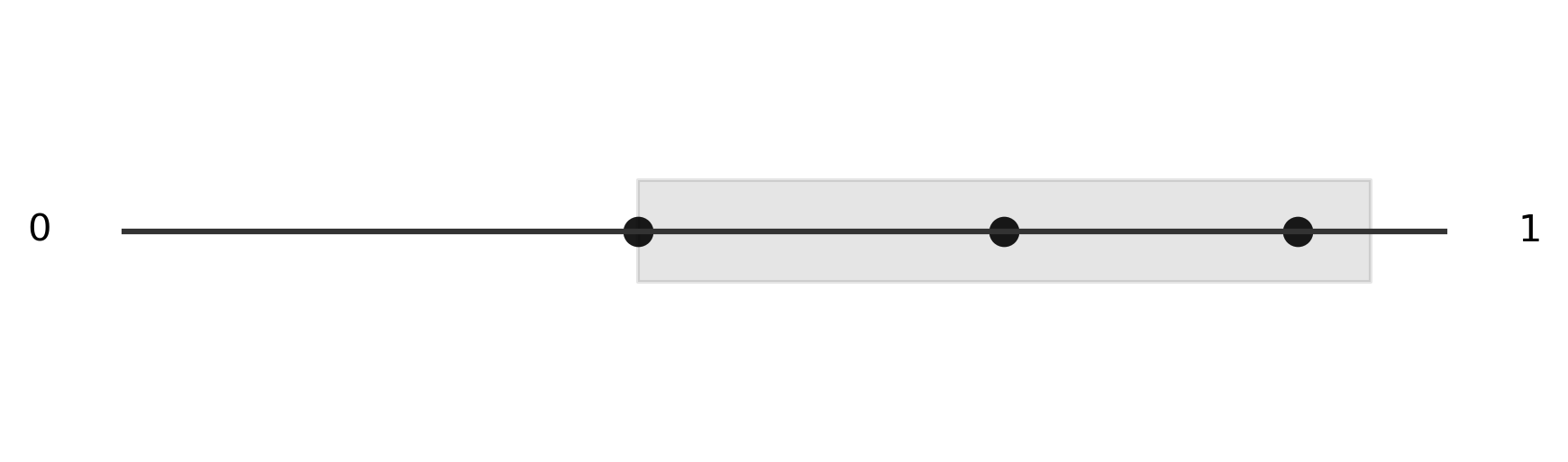

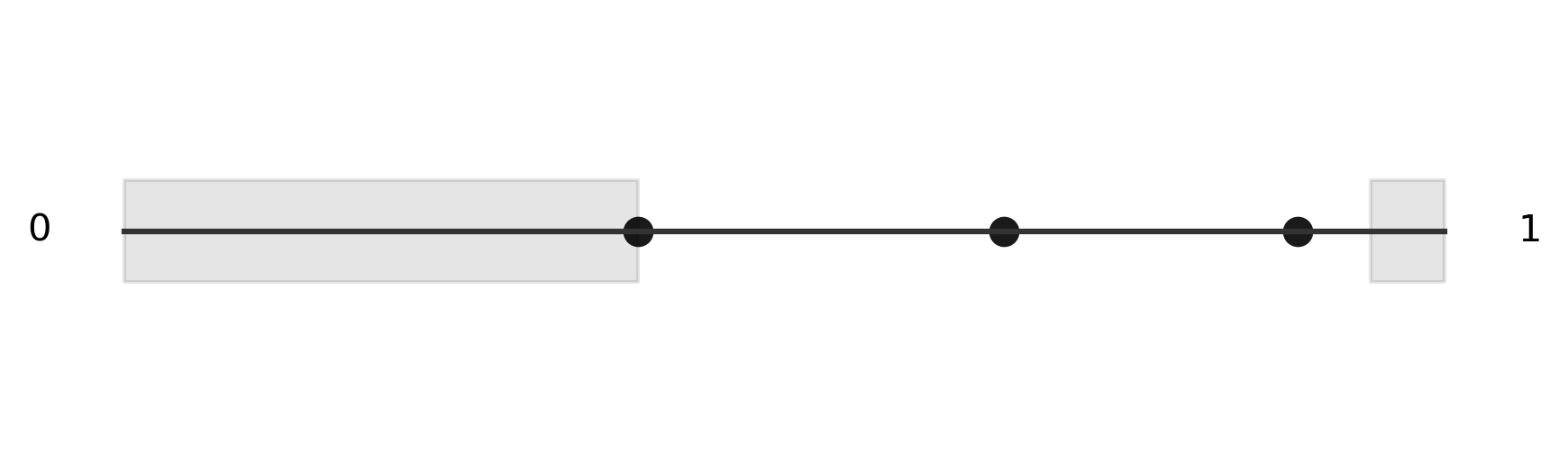

Calculating the criteria - we can imagine each point of the circle defining two different halves for us to check. If we find that every other point is contained in one of those halves, then we know our criteria is satisfied. To simplify this, we can imagine "cutting" our circle at the "3 o'clock" position and stretching it out into a number line.

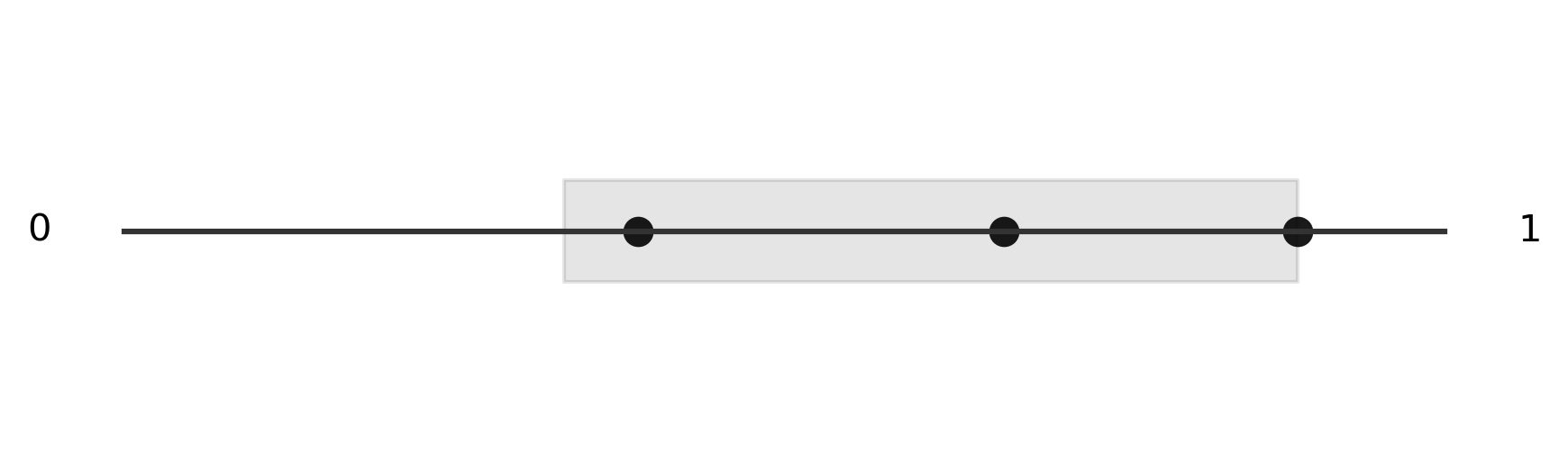

You can see that the points we generated around the edge are simply transposed onto the number line. Next, we generate both sides of each point, shown in grey, keeping in mind that we can wrap around each side of the number line, just like we would on the circle. Thankfully, we can use modular arithmetic to do this "wrapping" automatically. The next several images show the two halves we generate from two of our random points. We see that in at least one case, we found a single region that contained each of the three points, so we consider this simulation a success.

Because this is a simulation, we want to generate many trials and count the number of successes. If we divide the number of successes by the total number of trials, we get an approximation of the true rate of success. Here is the Python function that implements our simulation.

What is neat about this code is that we can run all of our simulations simultaneously. This is an example of vectorized code. Vectorized code is often significantly faster than similar code implemented using loops. This code runs one million trials nearly instantly.

def model(n, trials=1000000):

"""

Solves the Riddler Classic from April 19, 2019

First generates a random number array of shape (trials, n). Then

calculates the distance between each point in the array from each

other point, wrapping around one or zero, just like a circle.

Using these distances, we calculate the minimum distance that

encompasses all points in the array. If the minimum distance is

less than 0.5, we return True, otherwise False. The function then

returns the sum of all True values divided by the number of trials

to estimate the probability for a given value of n.

"""

r = np.random.rand(trials, n)

r = (r[:, None] - r[:, :, None]) % 1.0

r = r.max(2).min(1) < 0.5

return r.sum() / trials

Results

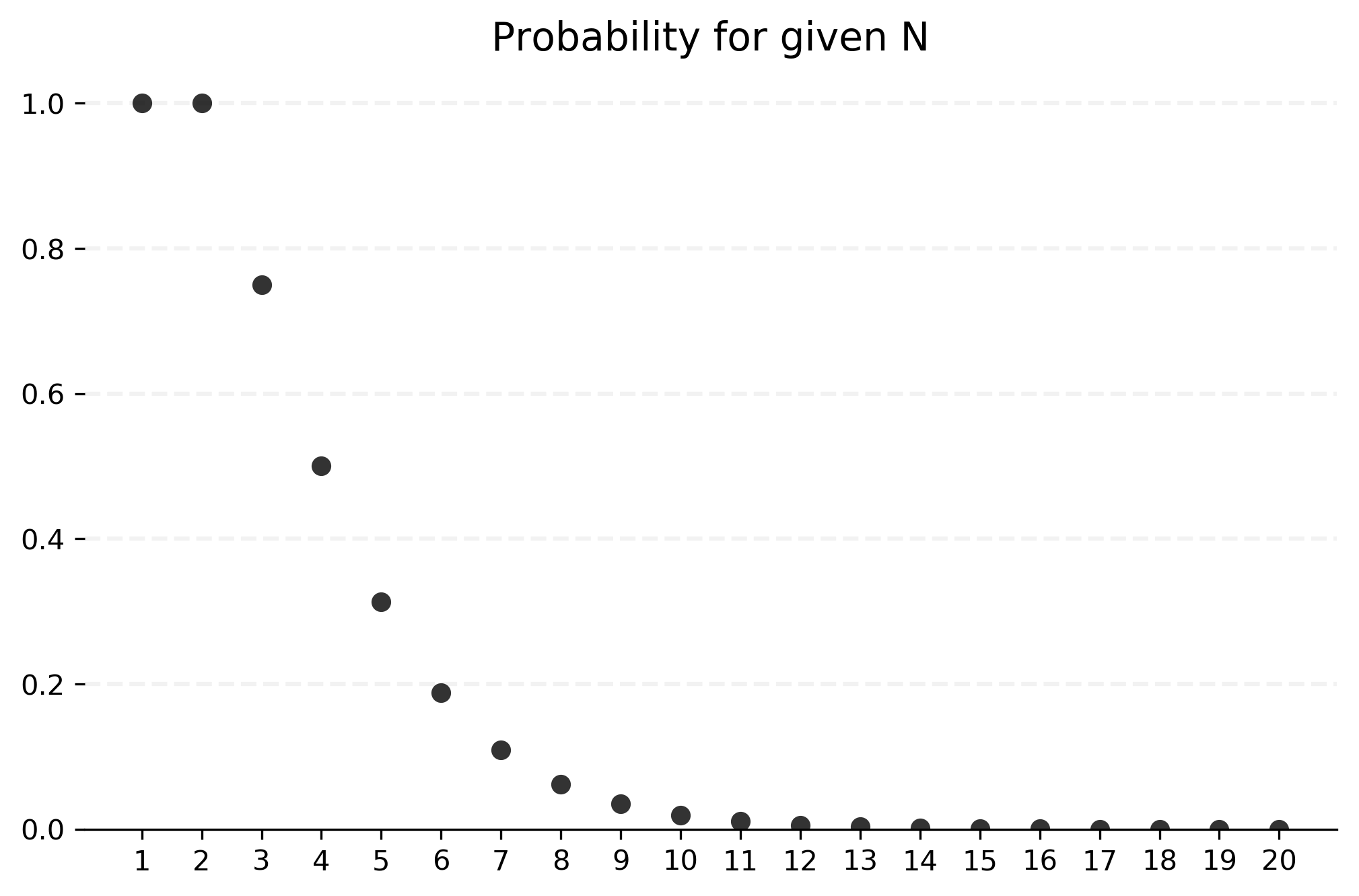

Using this function, we can test success rates for several values of .

results = {n: model(n) for n in range(1, 21)}

print(results)

{1: 1.0,

2: 1.0,

3: 0.749476,

4: 0.500362,

5: 0.312846,

6: 0.188008,

7: 0.109496,

8: 0.062215,

9: 0.0348,

10: 0.01946,

11: 0.010781,

12: 0.005754,

13: 0.003154,

14: 0.001721,

15: 0.000897,

16: 0.000491,

17: 0.000237,

18: 0.00013,

19: 7.1e-05,

20: 4.4e-05}

As usual, we can also visualize these probabilities in a histogram, shown below. We see that probabilities decrease significantly, to roughly less than 1% once we reach 10 or more points. When we generate 20 points, it's virtually impossible for them all to be on a single side of the circle. This confirms our intuition from above.

This was another interesting, and deceptively complex problem. It's one that I'd like to come back to and attempt to find an analytical solution later.